A rare request beyond borders

When it comes to rare blood types, it’s a global effort to match need with demand and our ethnic ancestry has a major part to play.

A prime example of how our blood products save the lives of patients in Australia and beyond was seen recently, when a patient needed a rare blood type in Israel.

When a blood type is so rare that a matched donor for a vulnerable patient can’t be found in their own country, the call goes international — and we answered. Although this doesn’t happen often, we’ve helped patients in USA, Spain and New Zealand, to name a few.

“Lifeblood has been working on expanding our Rare Donor Panel to enable us to better support our diverse population in Australia. We have also been increasingly able to assist our colleagues overseas," explained Executive Director of Clinical Services and Research Jo Pink.

“Blood groups are inherited and can vary in frequency in different populations. What may be common in one population can be extremely rare in another."

Transcending geographical lines

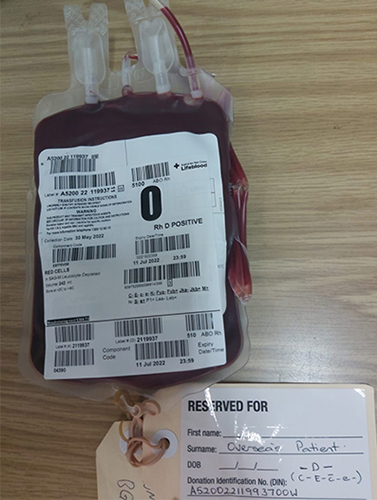

Recently we delivered a unit of exceptionally rare blood to Israel (pictured above on its arrival). The patient urgently needed blood transfusions of O positive, -D-, Jka- red cells before undergoing surgery. Now, you must be wondering: what do all those letters mean?

The most common blood groups include ABO (A, B, AB and O) and Rhesus (positive or negative). But there are a huge number (hundreds, even) of possible variations in blood type reflected in small changes on the surface of red blood cells. It can be important to accurately match these blood groups, especially for those who need frequent blood transfusions, like thalassemia or sickle cell anaemia patients.

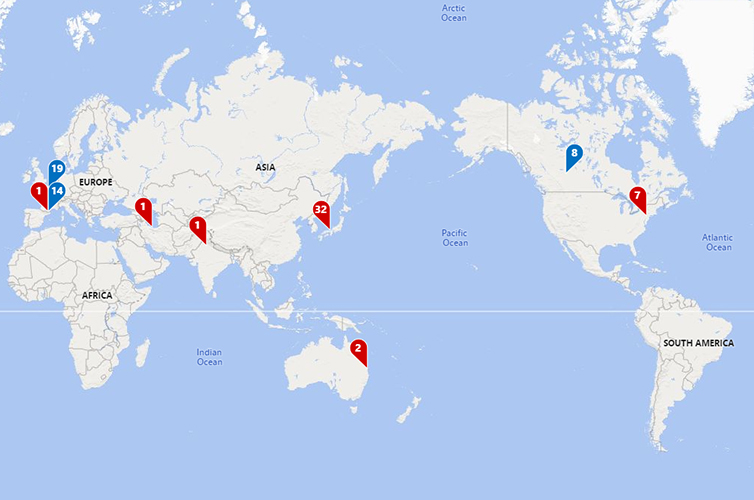

To put into perspective how rare the O positive, -D-, Jka- type is, there are only 44 donors listed on the International Rare Donor Panel with -D-. However, the red cells in this patient’s type also needed to be Jka-, which meant there were only two matched donors worldwide, one in India and one right here in Australia.

Luckily for us (and the Israeli patient!), the donor down under was identified with this rare blood type in 2015. Originally hailing from Bangladesh, they stepped up and donated the precious red cells at our Liverpool Donor Centre, which were then shipped to Israel.

This map shows the 44 donors on the International Rare Donor Panel that are group O and have the rare phenotype -D- (the blue flags show the number of frozen donations available). However, this patient also has anti-Jka so the red cells also needed to be Jka- meaning only the donors in India and Australia matched the requirements for this patient.

Effectiveness of ethnicity ancestry

It’s no surprise that 7.5 million people residing in Australia were born overseas, which is 29.1% of the country’s population. This directly corresponds to the diversity of people that may require blood products nationally, and in turn explains why their blood types matter. It’s an ever-evolving number and the challenge lies in meeting the needs of patients with rare blood types.

“The increasing diversity of our donor panel improves our chances of finding these special donors," said National Red Cell Reference Manager Tanya Powley.

Our Research and Development team recently explored ways to increase the diversity of our donor panel. One of the outcomes delivered was a study to test donors' responses to being asked about their ethnic ancestry. The study found that donors were very comfortable telling us their ethnicity and understood why it's important to us. The optional ethnicity ancestry question was introduced in the donor questionnaire in December 2020.

“While only a small number of donors have so far provided their ancestry information, we're able to use this, along with country of birth information, to target our testing to increase the chances of finding rare donors," Tanya said.

Increased donor phenotyping and genotyping has also increased the capacity of our Red Cell Reference team to identify rare donors. Between March 2019 and April 2022 the team genotyped 20,340 donors and identified 374 donors with a rare phenotype.

Think you might be one of our rare donors? Book a donation to find out.