The risks of transfusion-transmissible infections (TTI)

Risks of transfusion-transmissible infection calculated on Lifeblood data

| Agent and testing standard | Window period | Estimate of residual risk ‘per unit' (a, b) |

|---|---|---|

| HIV (antibody/p24 Ag + NAT) | 5 days | Less than 1 in 1 million [1] |

| HCV (antibody + NAT) | 3 days | Less than 1 in 1 million [1] |

| HBV (HBsAg + NAT) | 17 days | Less than 1 in 1 million [1, 2] |

| HTLV 1 & 2 (antibody) | 51 days | Less than 1 in 1 million [3] |

| vCJD [No testing] | Less than 1 in 1 million [4] | |

| Malaria (Plasmodium antibody) | 7–14 days | Less than 1 in 1 million [5] |

| Syphilis (T. pallidum antibody) | 30 days | Less than 1 in 1 million [6] |

Notes:

vCJD = variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease

(a) HIV, HCV and HBV risk estimates are based on Lifeblood data from 1 January 2023 to 31 December 2024 (or with an earlier start date where required).

(b) The HTLV risk estimate is based on testing data from 1 January 2011 to 6 December 2020 and donor/donation data from 1 January 2022 to 31 December 2023.

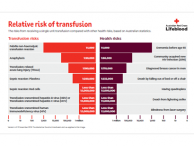

The relative risks of transfusion transmitted viral infections are very small compared to the health risks of everyday living (refer Relative risk of transfusion chart).

There have been no reported cases of transmission by transfusion of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (sCJD), and retrospective studies suggest that the possibility of such transmission of sCJD is remote [7-8].

In the UK, there have been a small number of reported cases of putative transfusion transmission since 2004. In the US, results from a 28-year lookback study reported no cases of CJD or prion disease in recipients [8].

To date, there have been no reported cases of vCJD in Australia. The risk of transfusion transmission resulting in a clinical case of vCJD in Australia in 2020 was estimated to be less than 1 in 1.4 billion per unit transfused [4].

References:

- Weusten J, Vermeulen M, van Drimmelen H, et al. Refinement of a viral transmission risk model for blood donations in seroconversion window phase screened by nucleic acid testing in different pool sizes and repeat test algorithms. Transfusion. 2011;51:203-215.

- Seed CR, Kiely P, Hoad VC, Keller AJ. Refining the risk estimate for transfusion-transmission of occult hepatitis B virus. Vox Sang. 2017;112:3-8.

- Styles CE, Seed CR, Hoad VC, et al. Reconsideration of blood donation testing strategy for human T-cell lymphotropic virus in Australia. Vox Sang. 2017;112:723-732.

- McManus, H, Seed, CR, Hoad, VC, et al. Risk of variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease transmission by blood transfusion in Australia. Vox Sang. 2022;117:1016-1026.

- Schenberg K, Hoad VC, Harley R, Bentley P. Managing the risk of transfusion-transmitted malaria from Australian blood donations: Recommendation of a new screening strategy. Vox Sang. 2024.

- Jayawardena T, Hoad V, Styles C, et al. Modelling the risk of transfusion-transmitted syphilis: a reconsideration of blood donation testing strategies. Vox Sang. 2019;114: 107-116.

- Holmqvist, J, Wikman, A, Pedersen, OBV, et al. No evidence of transfusion transmitted sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: results from a bi-national cohort study. Transfusion, 2020;60:694-697.

- Crowder LA, Dodd RY, Schonberger LB. Absence of evidence of transfusion transmission risk of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in the United States: Results from a 28-year lookback study. Transfusion. 2024;64:980-985.

- What TTI residual risk estimates do we publish and where are they published?

We publish the TTI residual risk estimates in the Blood Component Information (BCI) booklet, and on this website. The viral risk estimates are reviewed and updated periodically. Our estimates are based on published methods.

- In very simple terms, what is the basis of the model calculations?

HIV, HCV, HBV

The 'window period' (WP) is defined as the interval between infection and first positive test marker in the bloodstream. That is, blood collected in this period is infected but remains negative on testing.

The risk of transmission from WP donations is estimated for HIV, HCV and HBV, using:- Viral incidence, i.e. the rate of newly acquired infection among repeat donors;

- The average interval between incident donors’ positive result and previous negative result; and

- The probability of transmission to the recipient of a WP donation based on a number of factors, including the lower limit of detection of the NAT test, the volume of transfused plasma and the presumed ‘infectious dose’ of the infectious agent.

The total estimate of HBV risk includes both WP risk and the risk of occult HBV infection (OBI), which is derived by a separate model. OBI risk is associated with any NAT-negative donations that may have been collected before a donor is detected as having OBI. This includes:

- The number of such prior donations, i.e. the probability of non-detection of OBI by NAT; and

- The probability that these donations transmit HBV (derived from lookback studies, which determine the outcomes of recipients transfused with these donations).

HTLV

Repeat donors are no longer tested for HTLV except in specific circumstances. New infections in repeat donors therefore represent the main source of HTLV risk, which is estimated from:- The prevalence of infection among repeat donors before HTLV testing was ceased for this group;

- The number of years over which donors typically donate, and how many donations they give during this time; and

- The probability that leucodepletion of a component reduces the number of infected leucocytes to below the infectious dose.

- What is the rationale for using the above calculations?

WP-based models assume that the risk of collecting blood from an infectious donor predominantly relates to them being in the WP (i.e. incident infection) and the best estimate of incidence in the donor population is the rate of incident donors in the repeat donor population.

The Weusten model further assumes a concentration-dependent probability that the virus is not detected in the log-linear ramp-up phase of plasma viraemia in acute infection, and a dose-dependent probability that an infection develops in the recipient of the contaminated blood product. Both these probabilities contribute to the overall residual risk.

While the assumption that WP donors account for the majority of risk seems to hold true for HIV and HCV, HBV is problematic because of 'chronic' infection (i.e. HBsAg negative/anti-HBc positive with low levels of HBV DNA). WP-based models do not satisfactorily address the risk of long-term OBI. Therefore, Lifeblood developed a specific model to estimate the OBI risk which is summed with the WP risk to derive the overall HBV residual risk estimate. Importantly, HBV NAT will incrementally identify OBI donors since the vast majority can be detected using the highly sensitive ID NAT employed by Lifeblood.- How do these residual risk estimates compare to the risks associated with everyday living?

When considering the significance of specific risks, it is useful to compare them to the risks associated with everyday living. Levels of risk are compared in this Calman Chart.

The Calman Chart for Explaining Risk (UK risk per 1 year)Classification Risk range Example Negligible <1:1 000 000 Death from a lightning strike Minimal 1:100 000–1:1 000 000 Death from a train accident Very low 1:10 000–1:100 000 Death from an accident at work Low 1:1000–1:10 000 Death from a road accident Moderate 1:100–1:1000 Death from smoking 10 cigarettes per day High >1:100 Transmission of chickenpox to susceptible household contacts Source: Calman K. Cancer: science and society and the communication of risk. BMJ 1996;313:801.

The chance of dying in a road accident, for example, is about 1 in 10 000 per year which is considered a ‘low’ risk. Comparatively, all our viral risk estimates are well below this level, and would be classified as a ‘negligible risk’.The relative risks of transfusion-transmitted infections are also very small compared to the health risks of everyday living (refer Relative risk of transfusion chart).